Jerry Bransford

By: Jezreel M. Amica

For Jerry Bransford, being a tour guide at Mammoth Cave doesn’t just put bread on the table. It fulfills his sense of purpose of keeping alive his ancestors’ legacy.

Following one of his numerous tours that included members of the Western Kentucky University Xposure journalism workshop, Bransford talked about his family’s relationship to the world’s longest cave system and why he works there.

“I thought I needed to be here,” he said, clad in a park ranger uniform, smiling from ear to ear.

Bransford, from Glendale, Ky., said he felt an obligation to speak for his “kin folk,” who once worked inside Mammoth Cave as slaves.

Bransford spoke passionately about how Mammoth Cave became a tourist attraction. He said his ancestors, who worked tirelessly in the cave for mere pennies, were “quietly sent away.”

Bransford believed racism was to blame. In an interview in American Legacy magazine, the tour guide talked about his father’s account of how his ancestors lost their jobs following slavery.

They were one by one, called into a manager’s office and told they would lose their jobs, when the National Park Service took over, he recalled. That was in the 1930s.

Bransford, who worked in corporate America for several years, said the legacy of his “kin folk” had started to fade.

It’s why he came out of retirement.

“I don’t want it to go away this time,” he said.

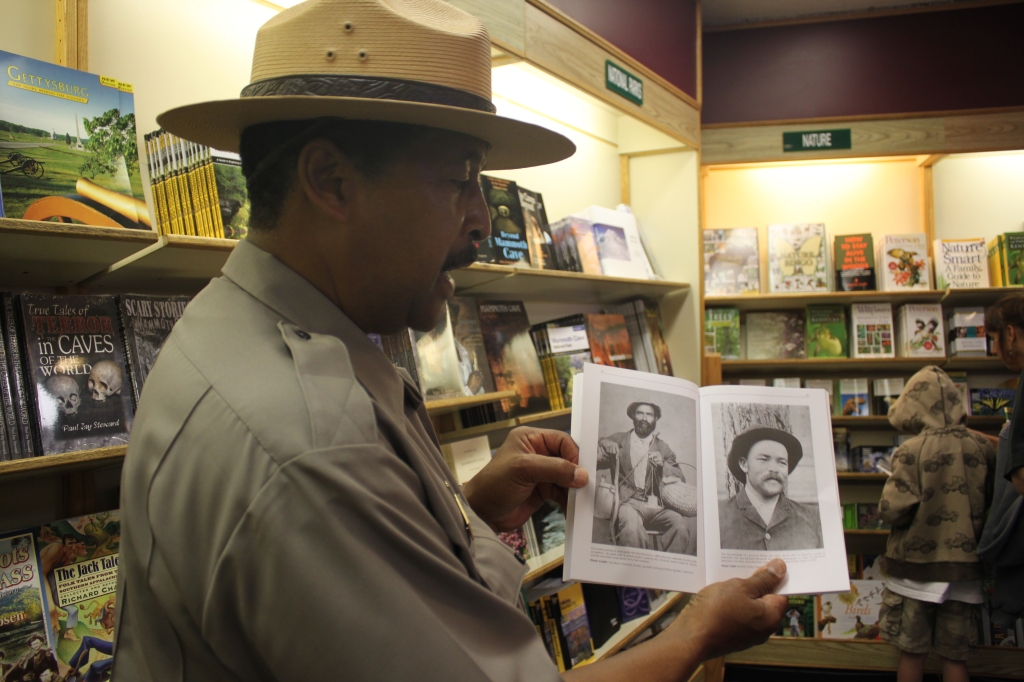

Bransford is a fifth generation tour guide at Mammoth Cave. He is the great- great-grandson of Matterson “Matt” Bransford, one of the three original Mammoth cave guides, all of whom were slaves in the 1830s.

Bransford leads animated tours that seem to bring his long dead ancestors to life. Some guests seemed to be inspired by his heart-felt accounts of the slave trails.

“I enjoyed his insight and knowledge of the history of the cave. It was actually pretty cool,” said John Stepp, 17, a high school student from Louisville, Ky.

At one point during the cave tour, Bransford told everyone to turn off cameras and cell phone lights and asked if anyone had a lighter.

He then gave the crowd simple instructions.

“When I count to one, I want you all to be quiet and very still,” he said, almost in a whisper, the anticipation building.

“When I count to two, close your eyes. When I count to three, open them. If you’re afraid of the dark, just skip number three and it will feel just the same,” said Bransford with a shout.

The crowd laughed.

“Alright ready… one.”

Silence descended upon the massive group. “Two…” he shouted.

All eyes closed.

“Three,” said Bransford, while eyes flew open and shrieks pierced the silence of the cave.

In the complete darkness, tourists couldn’t even see their hands in front of them.

Bransford told the crowd that for the slaves, the only way to avoid being engulfed by the dark was using candles to travel throughout the cave.

He then lit a single candle – his silhouette cast across the glistening cave wall.

“If all else fails, this one candle is enough to get us through to the cave entrance,” he said.

”And by us, I mean me and my assistant park ranger.”

It was Bransford’s easy humor and passion about the cave that impressed many visitors.

“Jerry is the best guide we’ve had so far,” said Jane Strayer, one of hundreds on hand for the tour.

“We’ve been here four times. He has such a connection to the cave. Everyone else is energetic and spirited, but he has the connection. He personalizes it. It’s surprising,” she said.

At 63, this tour guide said he doesn’t know how much longer he’ll be leading the tours. He has a daughter who has expressed interest in following in her father’s footsteps.

In the meantime, the man who has spent his life preserving the past is determined to make sure his people are never forgotten.

“No one can make them go away,” he said, staring at the spot where his ancestors once stood. “I won’t let them.”

Visitors enter the mouth of Mammoth Cave and feel the temperature drop immediately while descending the stairs. The farther visitors venture into the caves, the more the temperature changes. It can fluctuate anywhere from 6 degrees above or below 54 degrees Fahrenheit.

Jerry Bransford, tour guide for Mammoth Cave National Park, shows visitors a picture of his ancestors, Materson “Matt” Bransford, and William “Will” Bransford, 2 important figures to the early history of Mammoth Caves.

Jerry Bransford, tour guide for Mammoth Cave National Park, holds up a lighter in reference to resources used by tour guides in the early days of Mammoth Caves. Early tour guides used to take visitors through the caves using only the light of a single candle.

The figure of Jerry Bransford, Mammoth Cave National Park tour guide, silhouettes against the wall of the cave as he leads a tour through one of the many trails inside Mammoth Caves.

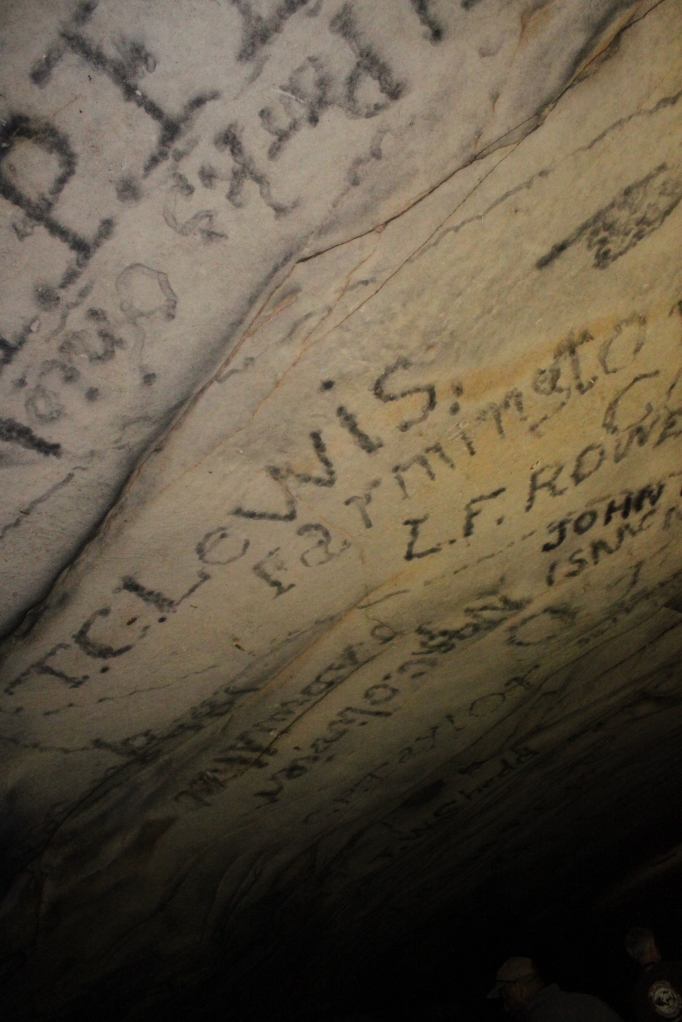

While touring Mammoth Caves, some of the walls hold ancient signatures from workers and tourists alike. Names were burnt into the cave walls with torches back before it was made illegal to deface the caves. This was a welcome pastime up until the ‘60s.

Xposure journalism workshop participants crouch to avoid walking into one of the many lower parts of Mammoth Cave National Park.

Shake Rag

By: Simone Palmieri

At least three times a year, the owner of the Shake Rag restaurant, the Rev, Roger Reed, gives back to the community.

“He gives the free food to anyone, whether they live here not, whether they are regular customers or complete strangers,” said waitress and Shake Rag community resident Christine Barnett.

Even regular customers may not know the historical significance of what they’re stepping into when dining at the Shake Rag Restaurant.

The Shake Rag District has been working several years toward revitalizing its community.

Those who settled what is now known as Shake Rag were former slaves, families and soldiers that supported the Union during the Civil War.

The name ‘Shake Rag,’ is speculated to originate from early African American families who washed and hung clothes on a line to dry. Monday’s were ‘wash days’ and people could be seen outside shaking their laundry. The term ‘Shaking of the rags’ evolved into Shake Rag.

Shake Rag Restaurant, a quaint establishment located in the heart of Shake Rag District, has a comfortable atmosphere, according to customers Shirley Williams and Ora Bell.

Williams actually lives outside of the Shake Rag District, but once she tried Shake Rag, she said it was worth the trip.

It’s a good place to bring the family,” she said, smiling at the kids with her.

What was once a thriving community during the ‘30s-‘60s, began to decline in the ‘70s when the federal government started the Urban Renewal Program.

“The neighborhood really began to lose its identity when the Urban Renewal Program came out in the ‘70s,” said Bowling Green City Commissioner Joe Denning.

Although the purpose of this program was to increase residential production across the country, people were forced to sell their property and move, so the community began to deteriorate, losing its thriving atmosphere.

The government then attempted to take the ‘hood’ out of the neighborhoods in order to make them safer and ended up crushing many communities.

Selvin Butts, a long time resident of the Shake Rag community, said the focus of revitalization is on three main blocks: College, State and Max Hampton Street where new, affordable homes are being built to help re-populate the area.

As new businesses start to serve the new community residents, one anchor will be there.

“I can definitely see us here 10 years from now, unless, you know, something dramatic happens,” Barnett said.